The recent decision by the U.S. Supreme Court to let stand a ruling by New York District Court Judge Thomas Griesa could have a major impact in the world economic scene. The ruling favors Argentine creditors and it requires the Argentine government to pay the debt owed to bond holders who did not agree to the terms offered in a previous partial settlements (the “holdouts”). The continued effort of the Argentine government to fight the ruling is based on its lack of understanding of how independent courts operate.

The recent decision by the U.S. Supreme Court to let stand a ruling by New York District Court Judge Thomas Griesa could have a major impact in the world economic scene. The ruling favors Argentine creditors and it requires the Argentine government to pay the debt owed to bond holders who did not agree to the terms offered in a previous partial settlements (the “holdouts”). The continued effort of the Argentine government to fight the ruling is based on its lack of understanding of how independent courts operate.

Seven years ago, during a trip to Peru, I had the privilege of spending four days attending programs with Justice Antonin Scalia. It was the first time that a Supreme Court justice had gone to Peru. During his presentation, a panel discussion with some of the highest authorities of the Peruvian judiciary, Scalia said: “During my entire career as a federal judge and Supreme Court justice, which now spans 26 years, never once, never once was I was approached by someone from the executive or the legislative power to try to exert influence in a case that was before me in one of my courts.”

A journalist interviewed me at the end of Scalia’s visit and asked me what impressed me most about his lectures. I repeated the above story and the journalist said to me: “It must be difficult to find a man with the integrity of Scalia.” Sure, it is difficult to find human beings like Scalia, but the journalist mistakenly thought that the independence of the judiciary in the U.S. was a matter of one person, not an institutional trait. Peru’s judiciary is not noted for its independence.

The notion of an independent judiciary that would constrain the government is even rarer in Argentina. In the World Rule of Law Index, Argentina scores a dismal 0.35 out of 1 in the category: Limits to the Government by the Judiciary. Peru does not score much better, only 0.45, but is moving in the right direction.

As for most of its tenure, the Argentine government presided by Nestor and Cristina Kirchner, saw a judiciary system mostly subservient to government interests. Because of this it is natural that they would think the U.S. courts could also be manipulated. The Argentine government and negotiators don’t understand that U.S. federal courts are still independent. The politicization of the nomination process in the U.S. has not lead to the direct manipulation of the highest courts.

A few weeks ago, before the ruling, and as a last ditch effort, the Argentine government sent a delegation to lobby the Obama administration and the Washington-based international bureaucracies. They asked them to “intervene” on behalf of the Argentine government. It proved futile. After the ruling, which recognized the rights of the creditors, the first official response from the Argentine government was to publish a one page advertisement in the Wall Street Journal attacking the decision of the judge.

Other countries are watching this battle. In Peru there is more willingness to play by the rules. José Luís Sardón, one of the main hosts of Scalia’s trips to Peru, spent most of his academic life as an intellectual entrepreneur in the area of law. His law department, at the Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas, has acted as a high-level, non-politicized legal think tank. Sardón produced a journal, Revista de Economía y Derecho, which has been elevating the discourse on legal and juridical matters in his country. Unlike the Argentines, who were recently greeted with “bad” news, Peruvians were greeted with the refreshing news that the Peruvian Congress had approved the appointment of Sardón to the highest court of the land.

The end result of the Argentine debt dispute is not certain. Agustín Etchebarne, executive director of Libertad y Progreso in Argentina, and with ample experience in the investment world, believes that, in the end, Argentina will negotiate with the holdouts. The clock started ticking, and if it does not reach an agreement by the end of July, it will likely default. Complying with the law might not be as costly as the Argentine government assumes. The latter fear that if they offer a better deal to the holdouts, the deal has to be offered to the 92 percent who have agreed to worse terms. Etchebarne believes that since the government is not offering to pay, rather it is being forced to pay, that “it is not clear that judges will rule in favor of the other creditors.”

Steve Hanke, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, and a professor at Johns Hopkins University, stressed that Argentina needs to create a positive shock. Complying with the ruling should reduce the country’s risk and send signals to the world that Argentina is again open to true, not just crony, business. Etchebarne adds that from the energy to the agricultural sectors, and many others, there are abundant opportunities for investments in Argentina. Complying with the ruling might benefit the development of a healthier Argentinean economy in the near future.

Although it is hard to be optimistic about Argentina, the future of countries are not sealed. During the late 1980s, respected Latin American analysts were forecasting the disintegration of Peru as a nation. There is still much to improve in Peru but its country default risk runs today at 1.3 percent compared to 14.6 percent for Argentina.

The Argentine government might portray the hedge fund owners that represent most of the holdouts as greedy vultures, but few have been more voracious than the Argentine government authorities. They have speculated that their use of their arbitrary powers will allow them to continue with their practices with almost total impunity. It is the poor of Argentina who have paid the price for government policies that have taken their country to the lower places in the rule of law rankings. If the Argentine political and media pressure would have been able to sway a U.S. federal court it would have set an awful precedent and would have unleashed an increase of similar practices by other countries. On the other hand, the Supreme Court’s decision to let stand Judge Griesa’s ruling will make it more difficult for other countries to restructure its debts in an arbitrary and unjust manner. It should also lead to an improvement of the legal frameworks governing defaults by sovereign countries.

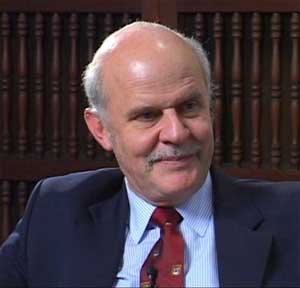

* Alejandro Antonio (Alex) Chafuen, Ph.D., has been president of Atlas Economic Research Foundation since 1991. A member of the board of advisors to The Center for Vision & Values and a trustee of Grove City College, he is also the president and founder of the Hispanic American Center of Economic Research. Dr. Chafuen serves on several boards including the Chase Foundation of Virginia, the Acton Institute, the Fraser Institute (Canada), and is an Active Honorary Member of the John Templeton Foundation.

Source: Forbes.com

Discussion

No comments for “Argentine Ruling Rocks The Sovereign Debt Market – by Alejandro Chafuen”